“How Christian Introverts Will Help Save the Church From Itself” is written by Joe Terrell, Carey Nieuwhof’s content manager and host of The Art of Leadership Daily podcast. Joe lives in Colorado with his wife and two cats.

You have a secret you’ve never shared with anybody:

You’ve always felt like an imposter at church.

At praise and worship services, you’d stand when you were expected to stand, sing along with the words on the projection screen, and sometimes even raise your hands with your eyes closed (most often during the key change at the song’s bridge).

But, if you’re honest with yourself (like, really honest), you didn’t do any of that because you felt a supernatural compulsion to do so. You did it because that’s what you thought you were supposed to do. You did it because you wanted to fit in.

On church retreats or at Bible studies, you’d listen to peers describe their relationship with Jesus like it was something out of a paperback romance novel, full of flowery prose and intimate yearnings, and you’d think to yourself, “I wish I knew what that felt like.” And when it came your time to share, you’d exaggerate spiritual experiences to match the energy in the room.

While listening to sermons, you could never turn the analytical part of your brain off. You’d sit in the pew, poking and prodding the message in your head, scanning for logical fallacies and strawman arguments. Sure, you were listening (very attentively), but probably not in the way the pastor would’ve appreciated.

I’d be willing to bet between one-third and one-half of people reading this blog post right now connect with at least one of the situations I’ve outlined above. Why? Because between one-third and one-half of people are introverts, and those examples came directly from my personal experiences growing up in the church.

When I turned 30, I started going to professional therapy. Honestly, it was long overdue. And one of the biggest revelations I learned about myself was that I’m an introvert.

Looking back, it seems so obvious. And understanding came as a huge relief and helped explain some of the reasons why I felt like an imposter for much of my religious upbringing

But it also dredged up some more uncomfortable questions, like:

- Why did I equate being a “good Christian” with being an extrovert for so long?

- How many other Christians quietly wrestled with shame for not living up to the “extrovert ideal” of their faith communities?

- And, perhaps most importantly, what can introverts teach us about living faithfully in an age of disruption, scandal, and instant gratification?

The Differences Between Extroverts and Introverts

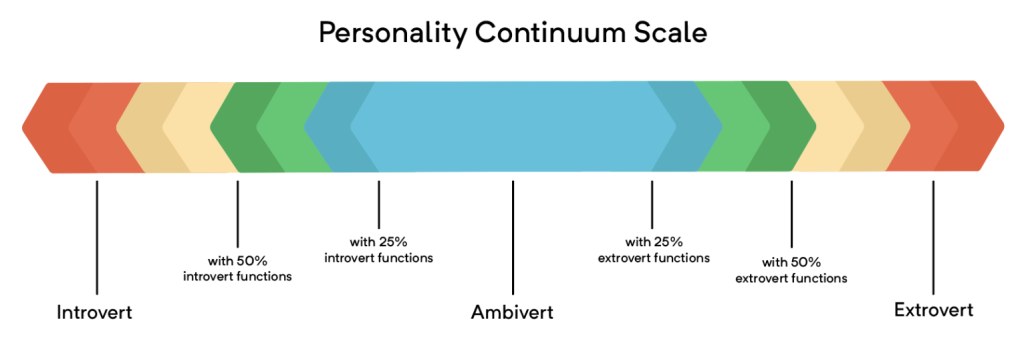

First things first: There’s no such thing as a “pure extrovert” or “pure introvert.”

Your predisposition toward introversion and extroversion sits on a scale (or spectrum), and most people are clustered around the middle with a preference for one side or the other.

Someone who leans more toward the introvert side of the scale will often find themselves drained by highly-stimulating environments and activities. Their temperament and personality orientate around the inner worlds of thought, introspection, and reflection.

An extrovert, in contrast, seeks out and is recharged by highly-stimulating environments and activities. Their temperament and personality orientate outward – toward external stimulation and social validation.

Some common characteristics of introverts include:

- An affinity toward reading, journaling, coding, painting, and/or writing

- Prefer working alone to group projects

- Gravitates toward corners at large social gatherings

- Feels more at home in a quiet bookstore than in a loud bar

- Will regularly leave events and parties early

For the record, to be an introvert doesn’t mean you’re a shy, awkward person who wants to be left alone all the time. Most introverts are incredibly charming, thoughtful, and passionate individuals – they’re just more conservative with their energy and more sensitive to their environments.

And, as I said above, we all carry some characteristics of introversion and extroversion. But some of our personality traits appear more “fixed” than others. Your temperament and personality are thought to result from a confluence of genetic, environmental, and neurological factors.

To be an introvert doesn’t mean you’re a shy, awkward person who wants to be left alone all the time. You’re just more conservative with your energy and more sensitive to your environment.”

Even from the beginning, easily agitated (or “highly sensitive”) infants appear to grow into more introverted adults. Physiologically, introverts tend to have thicker prefrontal cortexes compared to extroverts, a part of the brain associated with deep thought and decision-making.

Other studies reveal that certain neural pathways that help regulate the flow of sensory information to the cerebral cortex may be “wider” or “shorter” in introverts than extroverts, which could help explain why introverts are more quickly overwhelmed by their surroundings.

Extroverts also appear more sensitive to dopamine, the “reward” neurochemical that floods the brain in highly-stimulating environments and situations. Meanwhile, introverts appear more receptive to acetylcholine, a neurochemical that produces a feeling of “pleasurable calm” in moments of safety and quiet.

For anyone who has ever felt “less than” for not keeping pace with their extroverted colleagues, friends, or fellow brothers and sisters in Christ in highly-stimulating environments, the brief science lesson I shared above should come as a huge relief.

Or, as Adam McHugh writes Introverts in the Church,

“We can say that we are created as introverts. When our Creator knit us together, he shaped our brains in such a way that we would find satisfaction in reflection and comfort in a slower, calmer life.”

In other words, introverts aren’t the way they are because of some deficiency, lacking, or “sin” issue. Introverts are introverts because that’s the way that God made them.

In The Powerful Purpose of Introverts, Holly Gerth writes,

“When we turn inward, we’re not withdrawing or holding back; we’re choosing to show up in a sacred space of creativity, contemplation, and imagination. Our inner worlds are where insights, innovations, breakthroughs, solutions, and intimate connections with God originate.“

I firmly believe one of the most liberating truths an introvert can accept about one’s self is that a person’s relationship with God is not dependent on their brain chemistry or the strength of their feelings at a specific moment in time.

Introverts aren’t the way they are because of some deficiency, lacking, or “sin” issue. Introverts are introverts because that’s the way that God made them.

The Introvert and the Modern American Church

For those of us who “grew up in the church,” the expectation to conform (and perform) to extroverted expressions of faith often began early in “seeker-friendly” youth groups, hyper-energetic Christian summer camps, and heavily-produced evangelical megaconferences.

None of this, of course, was done with any ill intent (and, to be fair, some of it was very successful). Still, it led to a significant time in my life when participating in Christian events and activities left me emotionally, physically, and spiritually exhausted.

In You Are What You Love, professor James K.A. Smith writes,

“We have effectively communicated to young people that sincerely following Jesus is synonymous with being ‘fired up’ for Jesus, with being excited for Jesus, as if discipleship were synonymous with fostering an exuberant, perky, cheerful, hurray-for-Jesus disposition like what we might find in the glee club or at a pep rally.”

Even in my youth, it was obvious that some of my peers absolutely thrived in these highly energetic, competitive, and stimulating environments. I nursed feelings of jealousy at my extroverted counterparts and wondered why I couldn’t muster up the same level of zeal and passion. It must be a hidden sin issue, I thought.

From the frequency of “spiritual conversations” you should initiate with strangers to the expectation to “plug in” to event-based social ministry programs, the pressure to adopt extroverted personality traits in the church continues into adulthood.

Even the programming of most church services appears designed to minimize (or eliminate) opportunities for thoughtful contemplation, reflection, or lament to propel the participant toward the next “moment” in the service.

In A Long Obedience in the Same Direction, Eugene Peterson writes,

“There is a great market for religious experience in our world; there is little enthusiasm for the patient acquisition of virtue, little inclination to sign up for a long apprenticeship in what earlier generations of Christians called holiness. Religion in our time has been captured by the tourist mindset.”

If we’re not careful, we can subtly (or not-so-subtly) paint the picture that an authentic Jesus follower is relentlessly optimistic, tirelessly energetic, emotionally expressive, and magnetically sociable.

In other words, pure nightmare fuel for introverts.

Portraying Christianity as a gregarious social club of unbridled enthusiasm can be extremely off-putting for those of us who are easily overwhelmed and prefer thoughtful contemplation to expressive displays of religious affection. It can also appear incredibly performative and manipulative.

In Introverts in the Church, Adam Hughs writes,

“The upfront piety of evangelicalism and the expectation of outward, emotional displays of faith can feel invasive and artificial to introverts.”

This isn’t to say extroverted expressions of faith are somehow inferior to the spiritual experiences of introverts. Nor is it to say that the very Biblical mandate of evangelism and fostering community should be abandoned to coddle the sensitivities of introverts. But it is a challenge to evaluate the modern church experience through the eyes of roughly half the population.

If we’re not careful, we can paint the picture that an authentic Jesus follower is relentlessly optimistic, tirelessly energetic, emotionally expressive, and magnetically sociable.

In other words, pure nightmare fuel for introverts.

However, the question remains: Why are Christian introverts more likely to feel pressure to develop the personalities of Christian extroverts than the other way around?

If you were an introvert raised in an environment where extroversion was rewarded and introversion was something to be “fixed,” you may have – like me – become very good at “masking,” or performing, as an extrovert to fit in and succeed. These closeted introverts expend a lot of extra energy maintaining their facade and – I’m willing to bet – are far more prone to burnout.

Why are Christian introverts more likely to feel pressure to develop the personalities of Christian extroverts than the other way around?

But where did this pressure come from?

In Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Won’t Stop Talking, Susan Cain writes how most of us in Western society have been subtly indoctrinated into a value system she refers to as the Extroverted Ideal, or “the omnipresent belief that the ideal self is gregarious, alpha, and comfortable in the spotlight.”

Cain writes,

“Introversion is now a second-class personality trait, somewhere between a disapointment and a pathology…Extroversion is an enormously appealing personality style, but we’ve turned it into an oppressive standard to which most of us feel we must conform.“

Originating around the time people began moving from farms to cities in order to work in factories and office buildings at the dawn of the twentieth century, the Extroverted Ideal swept through America’s social institutions and became the gold standard by which the strength of one’s leadership’s ability and potential was judged.

And the church was no exception.

Under the “Christian Extroverted Ideal,” introverted Christians can intuit from their cultural environment that they’re simply too shy, quiet, stoic, dispassionate, or easily overwhelmed to be an “effective” follower of Jesus.

And those assumptions couldn’t be further from the truth.